Title: “Something is not right” – Progressive Cognitive and Behavioural Symptoms Post-CAR-T Therapy

Submitted by Alex Rampotas

Physician expert perspectives: Alex Rampotas

Academic Clinical Lecturer, University College London Hospitals, London, United Kingdom.

A 61-year-old man with a history of multiply relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL), previously treated with the UKALL14 protocol followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation and subsequent CD19-directed CAR-T cell therapy (obe-cel), presents with new-onset neuropsychiatric symptoms.

He has been in complete remission from B-ALL for the past two years. His recent immunological profile showed undetectable CD19+ B cells, persistently low immunoglobulin levels (requiring regular IVIG replacement), and reduced CD4+ T-cell counts (<0.2 x10⁹/L).

The patient was brought in by family due to subtle but progressive cognitive and behavioural changes. These included:

- Driving his car in reverse for many meters

- Parking in the middle of the street without realising

- Visiting his son’s home at 3 a.m. asking for milk

- Increasing forgetfulness and intermittent disorganized speech

On examination, there were no focal neurological deficits. His Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score was within the normal range, though collateral history was strongly suggestive of cognitive decline and altered behaviour.

Investigations:

- MRI Brain: Demonstrated a small area of T2-weighted signal abnormality in the deep white matter of the right parietal lobe, with associated diffusion restriction and focal contrast enhancement. Additional signal abnormality noted at the right ponto-mesencephalic junction.

- Lumbar Puncture showed no excess of lymphocytes and normal protein levels, while CSF PCR for infectious and autoimmune causes are currently pending.

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Anti-LG1 encephalitis

B. Potassium channel autoimmune encephalitis

C. JC Virus infection

D. B-ALL CNS relapse

E. Toxoplasmosis

Expert Perspective by Alex Rampotas

PCR from CSF fluid confirmed JC virus infection

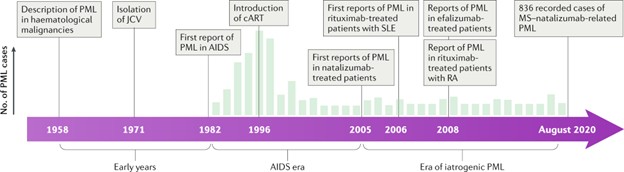

JC virus (John Cunningham virus) is a human polyomavirus named after the initials of the first patient in whom it was identified. It infects most individuals asymptomatically during childhood and establishes lifelong latency, primarily in the kidneys, bone marrow, and lymphoid tissues. A related polyomavirus, BK virus, causes bladder infections and is similarly named after the initials of the first described patient (though the full name is unknown).

In immunocompetent individuals, JC virus typically remains dormant. However, in the setting of profound immunosuppression—particularly in patients with severely reduced CD4+ T-cell counts, the virus can reactivate. Upon reactivation, it may cross the blood-brain barrier and infect oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, leading to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a rare but often fatal demyelinating disease of the central nervous system.

The virus has a neurotropic variant characterized by mutations in the VP1 capsid protein gene, which enhance its ability to enter the CNS and lyse glial cells. Once in the brain, JC virus replicates within oligodendrocytes, leading to their destruction and widespread demyelination. Astrocytic infection may further contribute to the inflammatory and degenerative pathology. JC virus seroprevalence increases with age, with 50–80% of adults showing evidence of prior exposure.1

PML is the principal clinical manifestation of JC virus infection and is almost exclusively seen in severely immunocompromised patients, like HIV/AIDS (particularly with CD4 <200 cells/mm³),post-transplant immunosuppression and patients on immunosuppression for malignancies. Outside the context of malignant disease and HIV, it presents a major clinical issue on patients with Multiple sclerosis on Natalizumab and similar immunomodulatory therapies.

PML is insidious in onset, with symptoms reflecting the location of CNS lesions: Cognitive impairment, motor deficits (hemiparesis, ataxia), visual disturbances (hemianopia, cortical blindness), dysphasia and less commonly seizures.

A diagnosis of PML relies on clinical suspicion, neuroimaging, and virological confirmation

MRI Brain: Classically shows multifocal, asymmetric, non-enhancing white matter lesions, without mass effect. Lesions are T2/FLAIR hyperintense and usually located in subcortical regions (parieto-occipital > frontal lobes), often sparing the cortex.

CSF PCR for JC virus DNA is highly specific with a sensitivity ~75–85%. A negative result does not exclude PML, particularly early in the disease.2

Management

There is currently no antiviral treatment proven to be effective against JC virus. Management strategies focus primarily on restoring immune function, tailored to the underlying cause of immunosuppression.

HIV-Related PML

In patients with HIV/AIDS, the cornerstone of treatment is the initiation or optimization of antiretroviral therapy (ART). While immune reconstitution can lead to clinical improvement, it may paradoxically precipitate PML-IRIS (immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome), characterized by worsening neurological symptoms due to an inflammatory response. In such cases, corticosteroids are often used to manage the inflammatory component.

In patients with PML arising from iatrogenic or disease-related immunosuppression (e.g., due to natalizumab, rituximab, chemotherapy, or post-transplant immunosuppression), management involves discontinuation or reduction of the offending immunosuppressive agents wherever possible. As with HIV-associated PML, corticosteroids may be indicated if there is clinical or radiological evidence of PML-IRIS.

Pembrolizumab, a PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor, is the most studied experimental therapy for PML in the setting of immune dysfunction. Although not approved for this indication, the largest published case series (Cortese et al., NEJM 2019) involved eight patients, of whom four showed clinical improvement after pembrolizumab therapy. The cases were a mixture of haematological malignancies post treatment as well as immunodeficiencies either acquired or congenital3. More recently, pembrolizumab was reported to be highly effective in a case of PML following CAR-T cell therapy, where the patient achieved a full recovery4. The reported risk of JC PML in CAR-T cell therapy is reported to be 0.9 in 1000 cases5.

Mirtazapine, an antidepressant with 5-HT2A receptor antagonism, has been used anecdotally. The rationale is based on the hypothesis that JC virus may use serotonin receptors to enter glial cells. While not curative, mirtazapine may have a supportive role in limiting viral spread in the CNS, though evidence remains limited6.

Recombinant interleukin-7 (IL-7) has been trialled in isolated cases as a means to enhance T-cell recovery in severely immunosuppressed individuals. It remains an experimental option, with sparse data and no standard protocol for use in PML7.

Prognosis

Despite supportive measures, PML remains a devastating disease, with a 1-year mortality rate of 30–50%. Early recognition and reversal of immunosuppression offer the best chance for survival. However, in patients where immunosuppression cannot be reversed (e.g., active malignancy or post-transplant status), outcomes are generally poor. Survivors often have significant long-term neurological deficits.

This gentleman received 3 cycles of Pembrolizumab but failed to respond. He deteriorated neurologically losing motor functions and cognitively and passed away 4 months since diagnosis.

Conclusion

While no definitive treatment for JC virus exists, pembrolizumab stands out as the most promising experimental therapy, especially in non-HIV-related PML. Supportive therapies such as mirtazapine and IL-7 have been used on a case-by-case basis. The emphasis remains on early diagnosis and immune restoration, which are currently the most important determinants of outcome.

Correct Answer – C. JC virus infection

References:

- Cortese, I., Reich, D.S. & Nath, A. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and the spectrum of JC virus-related disease. Nat Rev Neurol 17, 37–51 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-00427-y

- Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, Davis L, Koralnik IJ, Sejvar JJ, Bartt R, Major EO, Nath A. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013 Apr 9;80(15):1430-8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828c2fa1. PMID: 23568998; PMCID: PMC3662270.

- Cortese I, Muranski P, Enose-Akahata Y, Ha SK, Smith B, Monaco M, Ryschkewitsch C, Major EO, Ohayon J, Schindler MK, Beck E, Reoma LB, Jacobson S, Reich DS, Nath A. Pembrolizumab Treatment for Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 25;380(17):1597-1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815039. Epub 2019 Apr 10. PMID: 30969503.

- Mackenzie S, Shafat M, Roddy H, Hyare H, Neill L, Marzolini MAV, Gilhooley M, Marafioti T, Kara E, Sanchez E, Rees J, Lynch DS, Thomson K, Ardeshna KM, Laurence A, Peggs KS, O'Reilly M, Roddie C. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy following anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy: a case report. EJHaem. 2021 Aug 4;2(4):848-853. doi: 10.1002/jha2.274. PMID: 35845220; PMCID: PMC9281485.

- Goldman A, Raschi E, Chapman J, Santomasso BD, Pasquini MC, Perales MA, Shouval R. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients treated with chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood. 2023 Feb 9;141(6):673-677. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022017386. PMID: 36332168; PMCID: PMC9979708.

- Cettomai D, McArthur JC. Mirtazapine use in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Arch Neurol. 2009 Feb;66(2):255-8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.557. PMID: 19204164.

- Sospedra M, Schippling S, Yousef S, Jelcic I, Bofill-Mas S, Planas R, Stellmann JP, Demina V, Cinque P, Garcea R, Croughs T, Girones R, Martin R. Treating progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with interleukin 7 and vaccination with JC virus capsid protein VP1. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Dec 1;59(11):1588-92. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu682. Epub 2014 Sep 11. PMID: 25214510; PMCID: PMC4650775.

Future Clinical Case of the Month

If you have a suggestion for future clinical case to feature, please contact Anna Sureda.