September 2024 Clinical Case of the Month

Title: Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Post Kidney Transplant

Submitted by: Fernando Barroso Duarte

Physicians' expert perspective: Fernando Barroso Duarte, Karine Sampaio Nunes Barroso, Livia Andrade Gurgel, João Paulo de Vasconcelos Leitão, Beatriz Stela Gomes De Souza Pitombeira Araujo, Rafael Alencar da Nóbrega, Lucas Freire Castelo.

Nurse's expert perspective: Natália Costa Bezerra Freire

Haematology and Bone Marrow Transplantation Department, Universitary Hospital Walter Cantído (HUWC), Haematology and Hemotherapy Centre of Ceará (HEMOCE), Fortaleza-CE, Brazil.

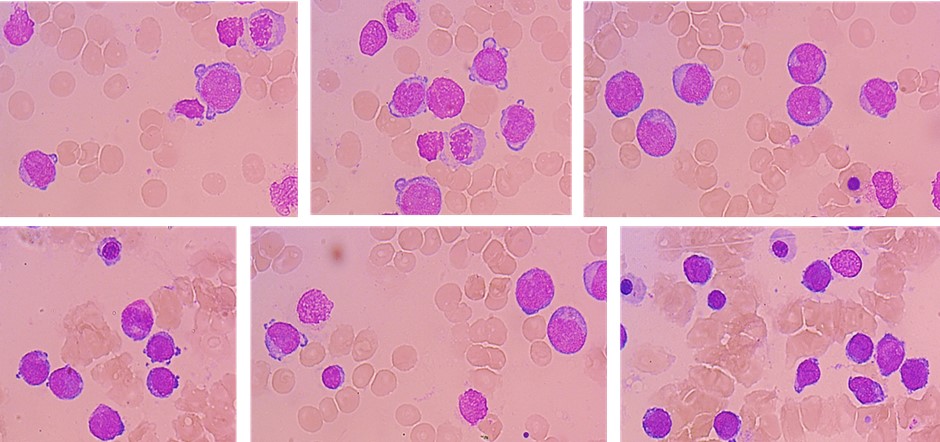

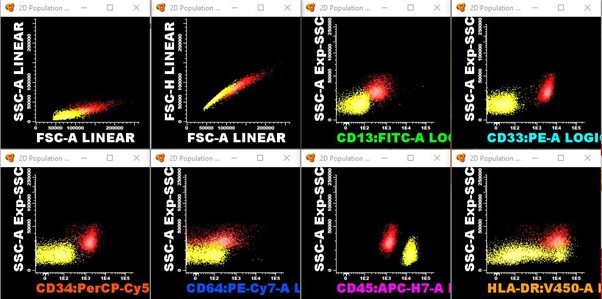

A 32-year-old woman who underwent a kidney transplant in 2015 from a deceased donor developed cytopenias while on immunosuppression with mycophenolate sodium and tacrolimus. Mycophenolate was then discontinued and low-dose tacrolimus and prednisone were retained. Due to persistent and progressive cytopenias, bone marrow aspiration and immunophenotyping were performed, showing 51% blasts (CD34+/CD33+/CD13+/MPO+/HLA-DR+), compatible with Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML).

Risk stratification was performed, with karyotype 46~47,XX,der(4),t(4;?),+8,+mar, unmutated FLT3 and NPM1, FISH negative for deletion of MLL and inv(16) and BCR-ABL negative, classifying as adverse risk due to complex karyotype. The patient underwent induction chemotherapy with 7 days of cytarabine 100mg/m² and 3 days of daunorubicin 60mg/m², with no renal graft dysfunction. The patient achieved complete remission. She underwent 2 subsequent cycles of consolidation with cytarabine 1,5g/m² every 12 hours on days 1, 3, and 5.

At pre-transplant evaluation, a measurable residual disease was identified by multiparameter flow cytometry (0,6% of abnormal myeloid precursors). She underwent haploidentical myeloablative peripheral blood HCT, with Busulphan/Fludarabine and PTCy/MMF/CsA prophylaxis. She had delayed neutrophil engraftment at D+27, and no platelet engraftment.

At D+30 evaluation, BM aspirate showed 13% myeloid blasts, 1,7% precursor with abnormal immunophenotype and full donor chimerism. MMF was discontinued, and we proceeded to Azacytidine 75mg/m² for 5 days followed by donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) 1x105.

How to manage immunosuppression in patients with Solid Organ Transplantation undergoing allogeneic HCT?

A. Discontinue immunosuppressive therapy (IST) before conditioning, and restart after Stem cell infusion and PTCy

B. Discontinue IST from day -1 to day +5 and maintain serum CSA level around 100ng/mL

C. Switch calcineurin inhibitor to mTOR inhibitor

D. Maintain serum CSA levels >150ng/mL

E. Proceed to transplant without additional immunosuppression, because we are using PTCy

Physicians' expert perspective:

Traditionally, in the treatment of AML, two phases of therapy can be distinguished: induction of remission (usually regimens with cytarabine and anthracycline) and consolidation with high-dose cytarabine followed or not by HCT (1).

However, the optimal treatment approach for myeloid neoplasms after SOT is unknown. Similarly, although allo-HCT is indicated in patients with therapy-related or high-risk cytogenetic AML, there are limited data in the literature on the role of allo-HCT in this clinical setting.

The feasibility of intensive induction chemotherapy is a challenge in post-SOT AML because these patients often have several limiting factors, such as age, performance status, CMV status and function of the transplanted organ, as well as increased treatment-related mortality (2).

Some specific possible complications should be taken into account, such as assessing dose adjustment of conditioning regimen, significant risk of rejection of the transplanted solid organ due to allorreaction between the allograft (the transplanted solid organ) and HCT donor-derived immune cells, and the possibility of not being able to interrupt IST to prevent rejection of solid organs from the allograft after allo-HCT, which can lead to opportunistic infections or recurrence of malignancies due to a weakening effect of the graft versus leukaemia (7).

In addition, the immunosuppressive microenvironment is marked by the presence of several immune evasion mechanisms, such as downregulation of antigen-presenting molecules, overexpression of inhibitory molecules, such as PD-L1 and Gal-9, and release of various immunosuppressive factors, such as reactive oxygen species. These factors can inhibit the cytotoxic function of T and NK cells, as well as induce T cell exhaustion and apoptosis. (3) Thus, considering the need to "restore immune surveillance," tapering off immunosuppressive medication is necessary, although it is often insufficient to achieve a CR (4).

Case reports and series report dismal outcomes, with median overall survival between 3 and 6 months, often attributed to early death, infection or relapse (4,5).

Allograft rejection is a major concern. The few case reports of patients undergoing allo-HCT after kidney transplantation for malignant or non-malignant diseases showed that renal failure was common and that increasing the dose of immunosuppressants helped to improve renal function only temporarily and did not prevent the need for dialysis (7).

The treatment of these cases has been heterogeneous (e.g., induction with intensive chemotherapy in those eligible with or without allogeneic stem cell transplantation or use of hypomethylating agents in association with venetoclax) (4,5,6).

Considering a high-risk disease in this case, a young patient with good functional status and preserved renal graft, we opted for induction chemotherapy with a 7+3 protocol, consolidation with cytarabine, followed by bone marrow transplantation. She received a graft from a young male haploidentical donor (in the absence of suitable matched related and unrelated donor), with myeloablative conditioning (9). During the initial follow-up, there was no decline in renal function or signs of renal graft rejection and successful bone marrow grafting.

In the published literature, IST management during the conditioning regime for HCT and after transplantation has been variable and often not reported. We chose to discontinue the IST during conditioning from day -1 to day +5 and restart with cyclosporine.

Our future plan will be to repeat bone marrow assessment and chimerism on the day 28 to define the start of the next cycle of azacitidine and schedule 3 more doses of DLI. We will maintain immunosuppression initially with cyclosporine in the target of 100ng/ml, monitoring viremia with PCR for weekly CMV, biweekly EBV and HHV-6, and BK virus at 30 days and at months 3, 6, 9 and 12 or as clinically suspected. We plan to manage the duration of the IST in conjunction with the kidney transplant team, aiming to return to the use of tacrolimus in order to preserve the function of the renal graft.

Nurse's expert perspective:

In Brazil, universal access to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is guaranteed by the Unified Health System (SUS). Our service is a reference in the Brazilian northeast, receiving patients referred from other states and regions of the country. This patient lives in a neighbouring state, which is 366 miles away, and it is possible to undergo chemotherapy treatment in our service, as well as HSCT.

The advent of haploidentical HSCT has made it possible to perform transplants for patients with high-risk acute leukaemia without related donors, given the greater ease of having a haploidentical donor among family members and being able to perform HSCT in a short period of time.

HSCT involves a complex therapeutic regimen that requires intensive care, especially in haploidentical transplants. Thus, nursing care begins before the transplant, with guidance to the patient and family about the HSCT process, possible complications and routines in the hospitalization unit. The patient in question was somewhat reluctant to attend the follow-up appointments and follow the instructions provided, stating that she had already had a kidney transplant and was knowledgeable about the medications and the transplant process.

During HSCT, the nursing team plays an essential role in direct patient care, safely administering medications, chemotherapy, immunosuppressants and blood components, managing the central venous catheter and acute toxicities related to therapy, in addition to offering emotional support to the patient and caregiver (8). In this particular case, due to the previous kidney transplant, the following were essential to nursing care: performing a strict fluid balance, monitoring body weight twice a day, monitoring kidney function through laboratory tests and the use of nephrotoxic medications, and adjusting immunosuppression, with the patient progressing satisfactorily without loss of the kidney graft. It is also essential that nurses be present to assist patients and caregivers with coping strategies when faced with negative perspectives of the transplant process, as happened with the patient, who required therapy with azacitide and DLI. At discharge and during outpatient follow-up, nurses should guide, assess, and monitor the patient regarding signs and symptoms of acute GVHD, enabling early identification and appropriate management.

The success of a therapy as complex as HSCT can only be achieved with a trained and interconnected multidisciplinary team, essentially the nursing team, as they are fully present in direct care for the patient and family. And in this unique case, the active participation of the nursing team was seen throughout the HSCT process.

Correct Answer: B

Acknowledgements:

Thays Araújo Freire de Sá, Hércules Amorim Mota Segundo, Ana Vitória Magalhães Chaves, Guilherme Rodrigues da Silva, Laís Chaves Maia, Mariana Saraiva Bezerra Alves, Mabel Gomes de Brito Fernandes Gomes de Brito Fernandes, Juliana Correa da Costa Ribeiro, Andrea Alcantara Vieira, Equipe de Transplante Renal do HUWC

References:

(1) Shai Shimony, Maximilian Stahl, Richard M. Stone. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2023 update on diagnosis,risk-stratification, and managemen. Am J Hematol.2023;98:502–526. DOI: 10.1002/ajh.26822.

(2) Anderson LA, Pfeiffer RM, Landgren O, Gadalla S, Berndt SI, Engels EA. Risks of myeloid malignancies in patients with autoimmune conditions. Br J Cancer. 2009 Mar 10;100(5):822–828.

(3) Xingmei Mu, Chumao Chen, Loujie Dong, Zhaowei Kang, Zhixian Sun, Xijie Chen, Junke Zheng, Yaping Zhang, Immunotherapy in leukaemia, Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica, Volume 55, Issue 6, 2023, Pages 974-987, ISSN 1672-9145, https://doi.org/10.3724/abbs.2023101.

(4) Rashidi A, Fisher SI. Acute myeloid leukemia following solid organ transplantation: entity or novelty? Eur J Haematol 2014; 92: 459–466

(5) Lontos K, Agha M, Raptis A et al. Outcomes of patients diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia after solid organ transplantation. ClinTransplant 2017; 31: e13052

(6) Thalhammer-Scherrer R, Wieselthaler G, Knoebl P, et al. Post-transplant acute myeloid leukemia (PT-AML). Leukemia 1999; 13: 321–6.

(7) Shinohara, Akihito et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Solid Organ Recipients with Emphasis on Transplant Complications: A Nationwide Retrospective Survey on Behalf of the Japan Society for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Transplant Complications Working Group. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Volume 26, Issue 1, 66 – 75.

(8) Kenyon, M., Murray, J. (2024). The Roles of the HCT Nurse. In: Sureda, A., Corbacioglu, S., Greco, R., Kröger, N., Carreras, E. (eds) The EBMT Handbook. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-44080-9_32

(9) Solomon SR, Sizemore CA, Sanacore M, et al. Haploidentical transplantation using T cell replete peripheral blood stem cells and myeloablative conditioning in patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies who lack conventional donors is well tolerated and produces excellent relapse-free survival: results of a prospective phase II trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(12):1859-1866. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.019

Future Clinical Case of the Month

If you have a suggestion for future clinical case to feature, please contact Anna Sureda.